Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) is a life-threatening metabolic emergency most commonly seen in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. It is characterized by extreme hyperglycemia, severe dehydration, and high plasma osmolality, with little or no ketoacidosis. If not recognized and treated promptly, HHS can lead to serious complications such as coma, organ failure, and death.

This condition often develops insidiously over days to weeks, making early detection challenging. Understanding the causes, symptoms, diagnostic criteria, and management strategies of HHS is crucial for patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals alike.

What Is Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS)?

Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State is an acute complication of diabetes marked by:

Very high blood glucose levels (often >600 mg/dL)

Marked dehydration

Increased serum osmolality

Minimal or absent ketosis

Unlike Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA), HHS does not typically involve significant ketone production or metabolic acidosis. However, the degree of hyperglycemia and dehydration is usually more severe.

Who Is at Risk of HHS?

HHS primarily affects:

Older adults with type 2 diabetes

Individuals with undiagnosed diabetes

Patients with limited access to water or impaired thirst response

People with chronic illnesses or infections

Common Risk Factors

Poorly controlled diabetes

Acute infections (pneumonia, urinary tract infections, sepsis)

Medications such as corticosteroids, diuretics, and antipsychotics

Nonadherence to diabetes treatment

Dehydration due to vomiting, diarrhea, or inadequate fluid intake

Pathophysiology of HHS

HHS develops due to a relative insulin deficiency, which is sufficient to prevent ketosis but inadequate to control blood glucose levels.

Key Mechanisms Involved

Reduced insulin activity → decreased glucose uptake by tissues

Excess hepatic glucose production → severe hyperglycemia

Osmotic diuresis → massive water and electrolyte loss

Progressive dehydration → increased plasma osmolality

Altered mental status due to neuronal dehydration

As dehydration worsens, renal perfusion declines, further aggravating hyperglycemia.

Signs and Symptoms of HHS

Symptoms often develop gradually and may be overlooked until severe.

Early Symptoms

Dry mouth and skin

Weight loss

Advanced Symptoms

Severe dehydration

Sunken eyes

Rapid heart rate

Confusion or delirium

Visual disturbances

Coma

Altered mental status is a hallmark feature and correlates with rising serum osmolality.

Diagnostic Criteria for HHS

Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and laboratory findings.

Typical Laboratory Findings

| Parameter | Finding |

|---|---|

| Plasma glucose | >600 mg/dL |

| Serum osmolality | >320 mOsm/kg |

| Arterial pH | >7.30 |

| Serum bicarbonate | >18 mEq/L |

| Ketones | Minimal or absent |

| Sodium | Normal or elevated |

| BUN/Creatinine | Elevated (due to dehydration) |

Additional Investigations

Serum electrolytes

Urinalysis

ECG and cardiac markers if cardiac events are suspected

Differentiating HHS from Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)

| Feature | HHS | DKA |

|---|---|---|

| Common in | Type 2 diabetes | Type 1 diabetes |

| Blood glucose | Very high (>600 mg/dL) | Moderately high |

| Ketosis | Minimal or absent | Significant |

| Acidosis | Absent or mild | Present |

| Dehydration | Severe | Moderate |

| Onset | Gradual | Rapid |

Management of Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State

HHS is a medical emergency requiring immediate hospitalization, often in an intensive care setting.

1. Fluid Replacement

The cornerstone of treatment.

Initial therapy: 0.9% normal saline

Gradual correction to avoid cerebral edema

May require 8–12 liters of fluid over the first 24 hours

2. Insulin Therapy

Low-dose intravenous insulin infusion

Initiated after partial fluid replacement

Goal: gradual reduction in blood glucose

3. Electrolyte Management

Potassium levels must be closely monitored

Hypokalemia may develop once insulin therapy starts

4. Identification and Treatment of Underlying Cause

Antibiotics for infections

Adjustment of medications

Treatment of myocardial infarction or stroke if present

5. Monitoring

Hourly blood glucose measurements

Frequent electrolyte and osmolality checks

Continuous cardiac monitoring

Complications of HHS

If untreated or poorly managed, HHS can lead to:

Thromboembolic events

Death

Mortality rates for HHS are higher than DKA, particularly in elderly patients with comorbid conditions.

Prevention of Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State

Preventive strategies focus on good diabetes management and early intervention.

Key Preventive Measures

Regular blood glucose monitoring

Adherence to prescribed diabetes medications

Adequate hydration, especially during illness

Early treatment of infections

Patient education on sick-day rules

Regular follow-up with healthcare providers

Living After an Episode of HHS

Recovery from HHS requires long-term diabetes management and lifestyle adjustments.

Post-Recovery Care Includes

Reevaluation of diabetes treatment plan

Nutritional counseling

Monitoring for complications

Education on recognizing early warning signs

Addressing barriers to medication adherence

With proper care, most patients can recover fully and prevent recurrence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main cause of Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State?

HHS is primarily caused by severe insulin deficiency combined with dehydration, often triggered by infection, illness, or missed diabetes medications.

Is HHS more dangerous than DKA?

Yes, HHS generally has a higher mortality rate due to severe dehydration, delayed diagnosis, and the older age of affected patients.

Can HHS occur in people without diabetes?

HHS can occur in individuals with undiagnosed type 2 diabetes, especially during acute illness or stress.

Why are ketones absent in HHS?

There is usually enough insulin present to suppress fat breakdown and ketone formation, unlike in DKA.

How long does recovery from HHS take?

Recovery may take several days to weeks, depending on severity, underlying conditions, and overall health.

Can HHS be prevented?

Yes, proper diabetes control, adequate hydration, and early medical care during illness significantly reduce the risk.

Does HHS cause permanent damage?

If treated promptly, most patients recover without lasting damage. Delayed treatment may lead to complications affecting the brain, kidneys, or heart.

Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State is a serious but preventable diabetic emergency. Its gradual onset often delays diagnosis, increasing the risk of severe complications. Early recognition of symptoms, prompt medical intervention, and effective diabetes management are essential to improving outcomes.

Raising awareness about HHS among patients and caregivers can save lives and reduce long-term health risks associated with uncontrolled diabetes.

#BhaloTheko

Disclaimer:

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.

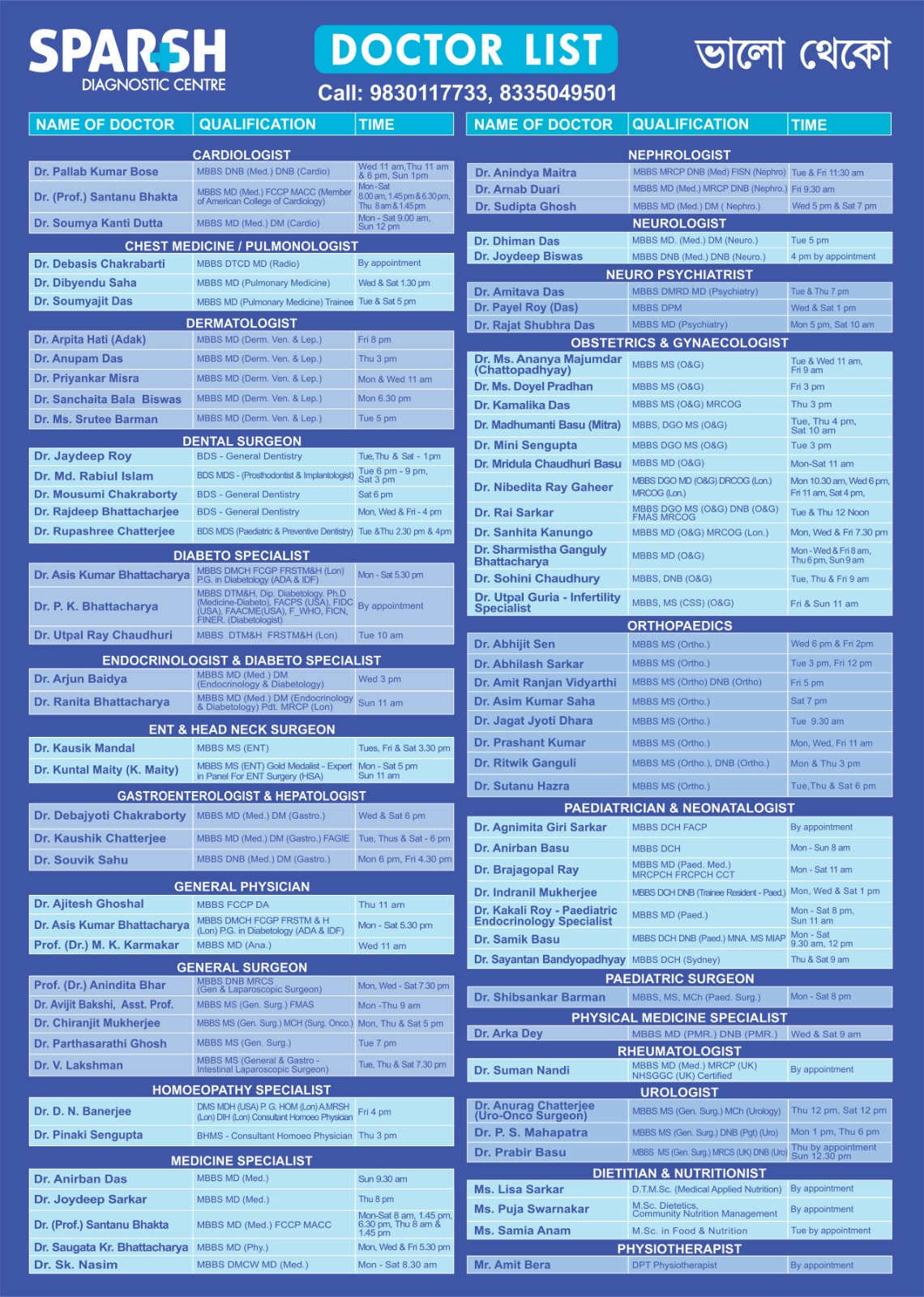

Sparsh Doctor List

![]()

[…] function. It often develops in individuals with uncontrolled diabetes, particularly in cases of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) or extremely severe hyperglycemia. Without prompt medical attention, this condition can lead to […]